The Poetry Class

As I have previously shared, I attended college at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina in 1971. Having grown up in the North, I had not experienced firsthand the open hostility of Whites toward Blacks in the South after the Civil Rights Movement. However that changed in the second semester of my first year, when I enrolled in a course on poetry. The course was taught by a White young woman, a graduate student, not much older than those of us in the class. And she was from Alabama, the significance of which will become apparent.

The year was 1972. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had been assassinated in Memphis only four years earlier. Civil unrest was present in many predominantly black communities. A year earlier in 1971, former King aide, Jesse Jackson had started Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity), an organization dedicated to continuing the unfinished work of Dr. King. In 1972 Barbara Jordan and Andrew Young became the first African Americans elected to Congress from the South since 1898. Shirley Chisholm, an African American Congresswoman from New York, announced she was running for President, the first African American to do so. Schools throughout the country, North and South, were being ordered to desegregate through mandatory busing. And Whites in the Old South, while clinging to their plantation and Confederate legacy, were resisting the change that was being called for at seemingly every turn.

The course I took that semester was an overview of English poetry beginning with Geoffrey Chaucer in the 15th century all the way up to 20th century poets like Robert Frost, T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats. The culminating project of the course was to research and write a paper on a poet of our choice, and to make a class presentation related to our paper. For my paper I chose the “bard of Harlem,” Langston Hughes. I don’t recall why I chose Langston Hughes, but I suspect it had something to do with my curiosity about the experience of African Americans in the U.S., and Hughes certainly fit the bill.

Who was Langston Hughes?

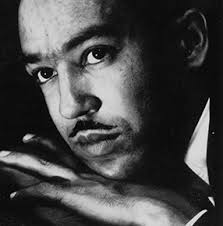

Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri in 1902 and spent his childhood in various communities throughout the Midwest. He began writing poetry while in high school in Cleveland, Ohio from which he graduated in 1920. He applied and was accepted at Columbia University, but only stayed there a year because of the of the overt prejudice of other students and teachers. However, while at Columbia Hughes must have wandered down the hill to Harlem where he encountered the vibrant cultural life of the African-American community. And while Hughes travel widely, even going to Russia and serving as correspondent in the Spanish Civil War, he always came back to Harlem. He eventually earned his B.A. degree at Lincoln University, an historically black college in Chester County, Pennsylvania. He then embarked on a career of writing travel logs, novels, essays, plays, and poetry.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

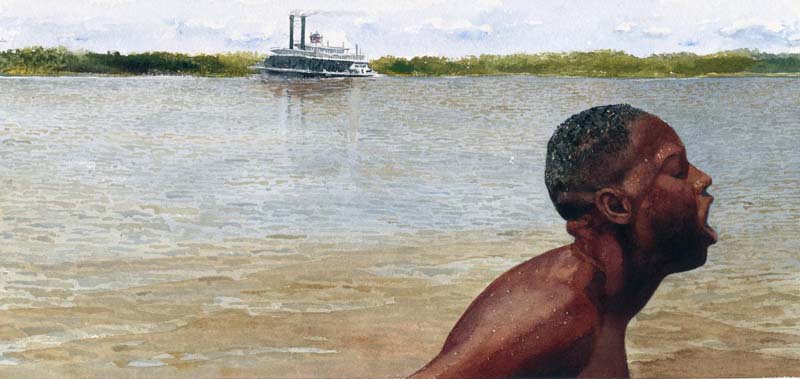

As I learned about Hughes, I became engrossed in his poetry. One of his earliest poems written when he was only 17 was “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” which relates the rich African heritage that runs in the soul of every black person in America

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom, all golden in the sunset

I’ve known rivers

Ancient dusky rivers

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

A Dream Deferred

I also encountered “A Dream Deferred,” a theme Hughes returned to often, how the American dream had not been meant to be given to the black community

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore –

and then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over –

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Jazz and Poetry

However, I confess what fascinated me most was how much of the poetry of Langston Hughes was set to a jazz or blues beat. For instance, the first lines of “Harlem Night Club” can only be read by snapping your fingers as you would to a jazz trio:

Sleek black boys in a cabaret

Jazz-band, jazz band –

Play, plAY, PLAY!

Tomorrow …who knows?

Dance today!

When I gave my presentation to the class, I read a few poems like this one, and as I read, had students snap their fingers to the beat, to get the feel. What I did not appreciate at the time was how poems like this for Hughes were not only descriptions of the what happened in a jazz club but also were testaments to the resilience of African- Americans, in a segregated oppressive society.

A Challenge to America

But perhaps one of his most enduring poems and most poignant is “Let America Be America Again” in which Hughes, like Frederick Douglass, James Baldwin and others, shines a light on the lie that is the American myth.

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

(It never was America to me.)

He then goes on to highlight all of those from whom the promise of America has been denied; the list goes on for two whole pages; here is a sampling:

(There’s never been equality for me,

Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”)

Say, who are you that mumbles in the dark?

And who are you that draws your veil across the stars?

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek—

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

After describing the plights of the poor and marginalized, he then comes to a close with an expression of hope and a call to action:

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!

Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death,

The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies,

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain—

All, all the stretch of these great green states—

And make America again!

My “Aha” About Racism

At the time, I did not grasp the profundity of his words and his social critique. However, what I did learn was not everyone in my poetry class shared my fascination with Langston Hughes – especially my instructor. Despite investing myself in the paper and delivering a presentation that had the whole class clapping and snapping, I received a “C” for the project. And the only comment from my White grad student-professor from the Deep South was “Langston Hughes is not a poet of note.” My instructor’s overt racism would not let her entertain the possibly that an African American poet could speak such words of passionate truth

Despite my disappointment with the grade, I intuitively realized that my instructor’s reaction to my paper was the kind of slight and prejudice that persons of color experienced every day at my school and throughout the country. While I was angry at the grade, it was more of an “aha” moment into the very discrimination Langston Hughes wrote about so elegantly, and the resistance to that discrimination he celebrated.

I never forgot Langston Hughes because of that poetry class, though I quickly gave up my idea of pursuing an English major; if this was the kind of professors I would have to deal with, I wanted none of it. I moved on to other things and more or less left Hughes and his poetry behind. However, many years later, I began reading the poetry of Langston Hughes again. The combination of life experience and a growing awareness of the influence of White Supremacy in all of American life has given me a deeper appreciation for his poetry and his life. In a sense it wasn’t just the words of poetry Langston Hughes that shaped me and impacted my life, it was also the reaction of my grad student- instructor. In spite of herself, my instructor helped me realize how prophetic, radical and needed the words of Langston Hughes were in 1972 and still are today.

Thanks Drick,

That’s a fascinating story. Thanks for including the poetry too,