Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will test and approve what is God’s will – God’s good, pleasing and perfect will. (Romans 12.2, The New International Version)

Don’t become so well-adjusted to your culture that you fit in without even thinking. Instead, fix your attention on God. You’ll be changed from the inside out. Readily recognize what God wants from you, and quickly respond to it. Unlike the culture around you, always dragging you down to its level of immaturity, God brings out the best in you, and develops well-formed maturity in you. (Romans 12.2 The Message)

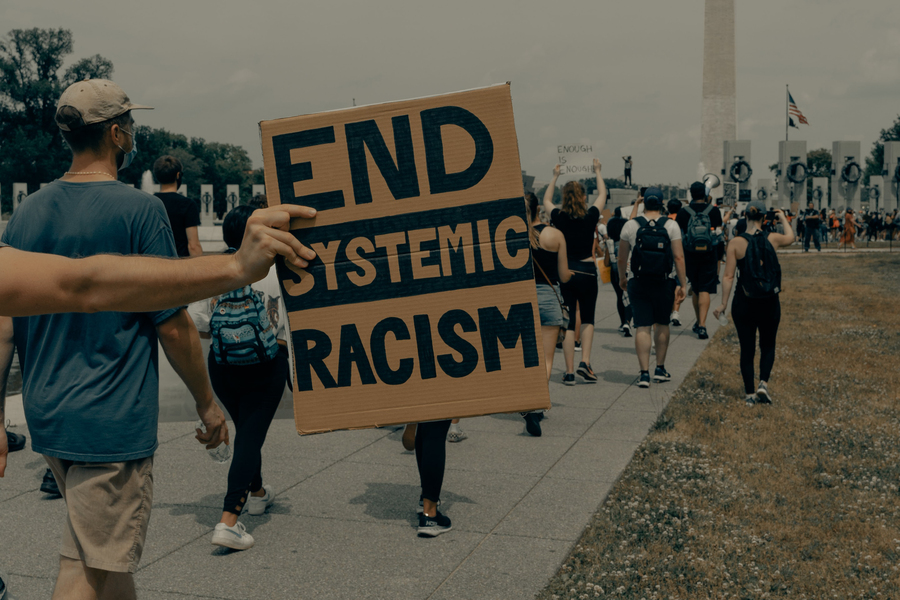

Systemic Racism

In my last blog, I indicated that racism does not just exist between individual persons (interpersonal racism), but also infuses many of our institutions and social systems, such that most people become blinded that an institutional practice, social policy, or social custom is inherently racist. To most people such things “just are;” they are normalized and therefore not critically analyzed. I concluded by suggesting that the work of antiracism begins with opening our eyes and minds to the racism that permeates our daily lives. The failure to open our eyes and hearts only deepens the divide and hardens the social denial of racism’s reality in our culture.

Because of the pervasiveness of racism infecting our institutions and social systems, it is both appropriate and accurate to call American culture racist. In saying American culture is racist, I am not speaking pejoratively or negatively about our culture, but rather descriptively. According to Ibram X. Kendi, a racist culture, like racist ideas, make People of Color feel less of themselves and white people more of themselves, or at least sends the message such feelings should be standard. So, in calling American culture racist, I am simply pointing out how our culture works and the messages it leaves various groups of people. Lest anyone doubt this is true of our society, one only has to look at the voluminous data that show that in nearly every aspect of life from education, criminal justice, healthcare, wages, and much else, BIPOC people fall way behind white people in every area. Such data confirms that racism is at the core of American culture.

This is true for both white people and BIPOC individuals. Whites can easily go through life oblivious to the social privilege and easier access to opportunities they have in relation to BIPOC folks. They live in a state of conscious or unconscious denial of the depth of suffering and loss experienced by those who face social barriers, overt and covert discrimination, and subtle but painful microaggressions every day. In both cases, whether one is white or BIPOC, this is considered to be “just the way things are,” and therefore unchangeable and inviolable.

EFFECTS OF RACIST AMERICAN CULTURE

In the words of The Message rendering of Romans 12.2, Paul says people are adjusted to their culture without even thinking. But the effect is well beyond just thinking; it also impacts their emotional life, physical health and their spiritual practices. They are left in a state of spiritual immaturity and blindness, falling far short of God’s desire for them.

And while one may think things just are as they are and cannot change, we must realize that culture, and leaders seeking to influence culture, actively oppose any effort by people to open their eyes. In recent months we have seen many examples of this resistance to critical analysis of our institutional policies and practices. School boards in many areas of the county have banned the reading of award-winning authors of color who share their experiences and perspectives. They have threatened teachers from presenting the full history of this country, a legacy of racism, land theft, genocide and exploitation of nonwhite people and the impact those events have on us today. Institutional offices of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) have been eliminated in some institutions. Courses on African-American and Latino history have been eliminated or have been gutted of any meaningful content.

These are the kinds of forces the Apostle Paul warns against being too well-adjusted to and instead calls us to resist and renew our minds with new eyes, new hearts and new commitments to justice and change. To not do so is to cause great harm to both white people and People of Color. For whites, the damage first takes the form of ignorance of our own history. I know in my case, any meaningful understanding of the role of racism in U.S. history did not come through my formal schooling, but rather was a result of learning outside the classroom and the mentoring from caring friends and mentors of color. But beyond ignorance is a looming sense of guilt and shame many whites feel when the topic of race comes up, which often expresses itself in what Howard Thurman called “resentful helplessness” and Robin DiAngelo labeled “white fragility.” Both Thurman and DiAngelo point out that when the topic of racism is raised, whites often experience feelings of discomfort, fear and anger. Because of these difficult emotions, whites often cloak themselves in righteous anger, denying any responsibility or accountability for the past and present instances of racial hate and exclusion.

For many BIPOC people, especially African Americans, the impact of America’s racist culture is damaging in other ways. For many Black individuals, there is a deep and abiding distrust of white people and the institutions that serve them that expresses itself in violence. Following the tragic death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Marches and demonstrations occurred in urban, suburban and rural communities across the country. A small percentage of those marches turned violent, leading to destruction and looting of stores and confrontations between protestors and police. Many media personalities referred to these actions as “riots.” But those much closer to the emotions that led to those acts of violence characterized them as “uprisings.” They cited Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who said such actions are “the actions of the unheard.” Overlaying the distrust and anger is an overriding sense of hopelessness. Hopelessness arises from a feeling that significant change will never come no matter what one does to improve his or her circumstance or station of life. In fact, many sociological experts attribute the current rise in violence, especially among young adults, as an outgrowth of this hopelessness.

If these effects are not troubling enough, both whites and BIPOC folks are often immersed and driven by their fear of the other group. This is why white people often purposely avoid neighborhoods and social spaces heavily populated by persons of color. It is why Black and Brown parents give their children “the talk,” in which they coach them how to respond to police officers and other white persons in authority, when (not if) they are stopped and accused of some wrongdoing. As Patrick Saint-Jean writes: “Today, none of us can avoid the ravages of racism, none of us can pretend or protest that it doesn’t exist in the United States. We are all victims of it, whether it affects us directly or indirectly. Whether we are Black, Brown, or white, we will all pay the price for our systemic racism.”

Spiritual Practice Focused on Systemic Racism

So what can we do? We must develop a set of spiritual practices focused on seeing, acknowledging, resisting and working to change the racist institutional practices in our society. As Paul says in the letter to the Romans, it involves the “renewing of our minds” or as The Message rendering of that same verse says, we must be “changed from the inside out. Readily recognize what God wants from you, and quickly respond to it.” This is what I have called Antiracism as Spiritual Formation.

Spiritual formation begins with a commitment to see and acknowledge that systemic racism influences almost every aspect of American life. It involves being aware and seeing through the cultural shadows and barriers that make it difficult to see the ways in which systemic racism affects us every day. In spite of the rhetoric that the U.S. is “the greatest nation in the world,” it is to acknowledge that we incarcerate more people per capita than any nation in the world, that babies die in childbirth at a rate greater than most other countries, and that a significant percentage of Americans have no access to quality health care. And while we claim to be the “land of opportunity,” it is to recognize that nearly 40% of the U.S. population lives below what would be considered a living wage (even those who are working two or three jobs just to survive).

In the end these are spiritual issues, issues about which we must pray, meditate, read Scripture, worship, and most importantly act, in the name of our faith. In so doing we will be practicing anti-racism as a form of spiritual formation. Rather than using our spirituality as a way to hide and escape from these harsh realities by focusing on personal salvation, it is to say that love and justice are as integral to the faith as taking Communion or praying the rosary. It is to see that all places are holy and all people are made in the image and likeness of God, and therefore worthy of our love, our compassion and our actions to make the world and our nation more inclusive and equitable for all, regardless of their race, creed or skin color.

SOURCES

Robin DiAngelo (2018) White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. New York: Beacon Press.

Ibram Kendi (2019). How to be an Antiracist. New York: Random House Books.

Patrick Saint-Jean (2021). The Spiritual Work of Racial Justice: A Month of Meditations with Ignatius Loyola. Vestal, NY: Anamchara Books.

Howard Thurman (1949/1976). Jesus and the Disinherited. Boston: Beacon Press

Howard Thurman (1965/1989). The Luminous Darkness: A Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope. Richmond, IN: Friends United Press.

Yes, racism is a spiritual issue, damaging the soul of our country (as MLK often said).

As long as we white folks remain in denial of our participation in racism, our spirituality is stunted, our souls are deadened