The Challenge of Empathy

In my recently released book Disrupting Whiteness: Talking with White People About Racism, I propose that the best way to engage white folks in conversations about racism is to take a dialogical rather than a confrontative approach. Too often conversations about race devolve either into meaningless debate or a complete shutdown and withdrawal from talking altogether. Instead of debate, I suggest that we ask people their perspectives about racism and then invite them to tell how they came to that perspective. I suggest that we encourage people to share their personal stories, and then listen empathetically, asking questions that attempt to draw out more of those stories. Rather than listening to find “flaws in their thinking, we listen to understand and in the process help the other person hear what they are saying and draw them into a conversation about why they feel as they do.

Speaking about this process of listening I write:

“When people tell their story, others must do what Stephen Covey calls empathic listening, which requires them to “seek first to understand, then to be understood.” He points out “most people don’t listen with the intent to understand, they listen with the intent to reply.” By contrast empathic listening seeks to understand other people’s perspective, to actually attempt to get inside their skin to understand how they see and experience the world….Empathic listening gives you credibility with others makes them more likely to hear your point of view.”

While I continue to believe that dialogue is the way we will breakdown the walls of division and polarization in our society on the issues of racism, recent events have caused me to realize how difficult and challenging empathy can be when a person sees and experiences the world in such a dramatically different way.

While I continue to believe that dialogue is the way we will breakdown the walls of division and polarization in our society on the issues of racism, recent events have caused me to realize how difficult and challenging empathy can be when a person sees and experiences the world in such a dramatically different way.

In a recent blog I shared my experience of seeking to enter a conversation with some devoted Trump followers who put forth wild and unsubstantiated theories as to why some Trump supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6. In a similar vein Republicans across the country are seeking to change voting laws, claiming there had been widespread voter fraud in November when there was and still is no empirical evidence to back up that claim. I am left wondering if these folks are purposely lying to hide their true motives, or that they are delusional. Neither option causes me to feel much empathy.

Exploring Empathy

In his book Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life, Dr. Marshall Rosenberg, describes empathy as “a respectful understanding of what others are experiencing.” He goes onto say that empathy requires not only listening but it demands “presence.” In speaking about presence he writes: “When we are thinking about people’s words and listening to how they connect to our theories, we are looking at people — we are not with them. The key ingredient of empathy is presence: we are wholly present with the other party and what they are experiencing.”

The key in being empathetically present to people is to listen between and beyond the words for the feelings, attitudes, needs and longings those words express. And when we respond, we do so by repeating back to them what we think we heard and allow them to either confirm or correct our response. Rosenberg says the paraphrased response invites the person to look within.

He also points out that sometimes our struggle with empathy is not that we can’t hear, but that internally we get triggered by something the other person says that causes our listening to stop. He counsels that as we listen to others, we simultaneously listen to what is going inside of us. He quotes former UN General Secretary Dag Hammarskjold: “ The more faithfully you listen to the voice within you, the better you will hear what is happening outside.” The power of empathy, when authentically practiced, is that it makes both the listener and the person who is speaking feel safer and more likely to continue talking. He writes: “When we listen for feelings and needs, we no longer see people as monsters.”

Once that openness and comfort are established, then tough conversations about racism or politics can proceed with respect and desire to understand. We experience an openness and receptivity to the other, even if we disagree with what they believe or affirm. That connection in itself can be transformative for both parties.

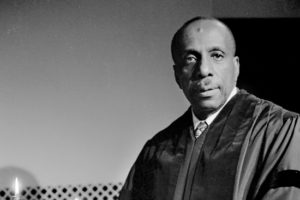

Loving and Oneness with the Other

The African-American Christian mystic Howard Thurman believed firmly in the oneness of all humanity even though he lived and ministered at the height of Jim Crow segregation in 20th century America. He challenged his listeners and readers to love the “other” no matter what. He described that love as “the experience through which a person passes when he deals with another human being at a point in that human being that is beyond all good and beyond all evil.” Thurman challenges us to move past walling off our adversaries but to remain empathetically open to what God or Spirit might do in the interchange.

Rosenberg and Thurman challenge me to see empathy as something much deeper than a technique or a set of skills with which to connect and influence people. They help me see that empathy, when followed to its natural end, helps us discover the common humanness connecting all people regardless of their race or circumstance or political opinion. At its heart racism — in whatever form — is a denial of another’s humanness. Polarization and hate are a refusal to affirm another’s essential human dignity. Shutting ourselves off from another also closes off something inside of us that affirms that other person as a being of worth.

I still believe that empathic listening enables us to cross boundaries of racism and polarization. Empathy does not mean we set aside our understanding of reality or truth, but that we also recognize that that truth is only as meaningful as we are able to respect and affirm the other, no matter how much we might disagree with them. And in the meeting of our souls, transformation can and will happen, as long as we are willing to follow the call to love the other to its natural destination.

Sources

Marshall Rosenberg (2003) Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life, 2nd Edition. Encitas, CA: PuddleDancer Press.

Howard Thurman (1971). The Search For Common Ground. Richmond, IN: Friends United Press