When I awoke on the morning of January 1, a huge cloud seemed to lift. I am sure I was not alone in being glad to put 2020 in the rearview mirror. Even so, the challenges and problems of 2020 have carried into 2021. The pandemic still rages, and thousands of people are dying every day. Donald Trump continues to try and foment rejection of a clear victory for Biden and Harris. And the calls for racial justice still continue.

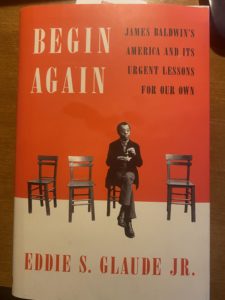

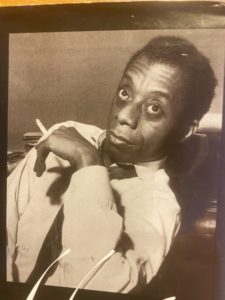

In his book, Begin Again, Dr. Eddie Glaude Jr. chronicles the life, writings, and legacy of James Baldwin, the small, Black gay man who was a voice of conscience in the 1960s and ’70s. Though Baldwin died in over 30 years ago, Glaude contends that his words have fresh and poignant meaning for our times. Glaude points out that the banners proclaiming Black Lives Matter were carried by Black activists young and old who had found a companion in the complex, tortured, and outspoken writer from Harlem. Just as he spoke to the lie of white supremacy in the mid-20th century, his words carry a similar relevance in the 21st.

Glaude portrays Baldwin as one who wrote from inside the struggle for racial justice, who lived, breathed, and agonized over the hatred, the violence and the death that came to so many working for theirs and others’ freedom. He deeply grieved the murders of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, and nearly took his own life in despair. And yet he persevered until cancer finally took his tortured weary life in 1987.

Reflecting on Baldwin’s angst, Glaude raises compelling questions:

“What might an honest reckoning with the country look like now? How do we muster the courage to keep fighting in the face of abject moral failure? To not abdicate our responsibility to fight for our children and for democracy itself? Baldwin’s later writings are saturated with these questions. He sought to answer them while grappling with his own trauma, grief, and profound disillusionment with the moral state of the country and in people who repeatedly choose the safety of being white over a more just society.”

Those final phrases I have highlighted grabbed me by the throat when I read them. Baldwin wasn’t talking in generalities, he was talking to and about me. He was disillusioned by progressively-minded, well-meaning, white people like me. As a middle-class white male, I have always had a choice whether or not to join the struggle for racial justice in our time. And even in joining the struggle, I do so from a place of privilege and (as Baldwin states) safety in my whiteness. Baldwin’s words challenge me to ask myself: Do I value my safety more than I value a just society? Do I draw the line at my discomfort and security? Are my calls for justice limited by my own self-interest? I sincerely hope not, but these are questions I must constantly put to myself.

In the summer of 2020 following the death of George Floyd, white people joined in numbers never seen before their with Black and Brown peers in marches and demonstrations for racial justice. Even in predominantly white cities like Portland, Oregon, young white folks protested police brutality for 100 continuous days. The joke in Portland was that there were more Black Lives Matter signs than Black people in Portland. Yet those white folks were there calling for change not only in Portland but across the country.

Then the summer ended and we entered a political campaign season that consumed many of us with fear, anger and a hope for a change in national leadership. While the focus had changed the goal of racial justice remained front and center as Donald Trump stoked the fires of white supremacist anger and hatred in his MAGA rallies. Many white folks along with BIPOC also contributed to that effort.

So now as we turn the page to 2021, it is important for those white folks who marched in the summer and worked for political change in the fall, to continue the effort. We may be weary of the battle, but we must remember for our colleagues of color that battle never ends and never subsides. We may have plans to pursue education or work or new experiences, but we must remember this work, the work of racial justice has not been completed. In terms of how social change happens and movements for the change ebb and flow, we are at a critical point. The forces of regression and white supremacy have been stoked by Trump’s madness, so we can not back down, we can not shirk our call, and we can’t lessen the pressure. In Baldwin’s terms, we who are white cannot retreat to the safety of our whiteness. Instead, we must continue the struggle in whatever settings and forum we find ourselves.

So now as we turn the page to 2021, it is important for those white folks who marched in the summer and worked for political change in the fall, to continue the effort. We may be weary of the battle, but we must remember for our colleagues of color that battle never ends and never subsides. We may have plans to pursue education or work or new experiences, but we must remember this work, the work of racial justice has not been completed. In terms of how social change happens and movements for the change ebb and flow, we are at a critical point. The forces of regression and white supremacy have been stoked by Trump’s madness, so we can not back down, we can not shirk our call, and we can’t lessen the pressure. In Baldwin’s terms, we who are white cannot retreat to the safety of our whiteness. Instead, we must continue the struggle in whatever settings and forum we find ourselves.

For some of us, that struggle will be in the streets, the courts, and the legislatures. For others of us, the struggle will be in the cafes, dinner tables and Zoom rooms with other white folks troubled and not so sure about these calls for change. Being about the work of racial justice is not a one-size-fits-all proposition, but it is something we are all called to and which calls us to stretch ourselves to the bounds of discomfort, frustration, courage, and fatigue.

While James Baldwin was a product of his time, many of his writings have a transcendent quality that can speak to our time. Baldwin’s life reminds us that the struggle for racial justice is ongoing, has not been won, and will not be finished anytime soon. Baldwin reminds us, to crawl out of our safe havens and stretch ourselves for the road ahead is long, steep, and continually challenging.