These days colleges and universities have come under increased scrutiny and criticism for (1) not adequately preparing students for employment upon graduation, and (2) for being too expensive for the average person to afford. So the question has been raised and debated, “Is a college education worth it?” As a faculty member at small, faith-based liberal arts university, I cannot stand aside from this debate since I am both a product and purveyor of higher education. However, it often seems to me that underlying these criticisms and the ensuing debate is another more fundamental issue, which is the relationship between colleges and universities and the communities in which they are located, and say they seek to serve.

The so-called “Town and Gown” tension has been widely advertised and been the subject or backdrop for any number of books, movies and even television shows like the current hit “How to Get Away with Murder.” At issue is the perception, rightly or wrongly, that institutions of higher education may employ members of the local community, but somehow see themselves aloof, and perhaps separate, from the communities in which they are located. To make matters worse, these non-profit institutions pay no property taxes while occupying large swaths of lands from which town and city councils could make revenue from if those lands were not so occupied.

In response to this criticism and dilemma, the Carnegie Foundation has developed an award that recognizes colleges and universities that seek to engage and serve their local communities. Students increasingly are encouraged to participate in service learning, internships and volunteer activities designed to serve the local community. There are now academic journals and organizations whose purpose is specifically to highlight university-community engagement. While these are all good things, all too often these efforts seem to use the community as a place of learning, service and research without really connecting in a meaningful way with the people who live in that community.

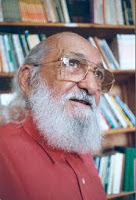

With these things in mind, I want to share some thoughts from the Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, whose book Pedagogy of the Oppressed is a standard, though often exoticized, text in many teacher education programs. In a series of letters to his niece, published as Letters to Cristina, Freire comments on the role he believes the university should have with the wider community beyond its campus. Given the current concerns about the value of higher education, I find his insights to be helpful and even profound. In the 12th letter of Letters to Cristina, he writes:

[T]he distance between the university (or what is done in it) and the popular classes should be shortened without losing rigor and seriousness, without neglecting the duty of teaching and researching… In order for that to happen the university must, if it hasn’t yet, increasingly become a creation of the city and expand its influence over the whole city. A university foreign to its city, superimposed on it, is a mind-narrowing fiction… [T]he university must start to be identified with its environment in order to move it and not just reproduce it…. These universities should cooperate with the state, towns, popular movements, production cooperatives, social clubs, neighborhood associations, and churches. Through such cooperation, the university could intensify its education action (Letters to Cristina, 1996, p. 133, 134)

What Freire is saying is that a college or university that only sees its mission as educating the students who enter its halls, has too narrow a vision. Learning is not an enterprise of the select few, but is part of what it means to be human. Thus, a university’s mission must extend beyond its walls to the wider community. In an age when local school districts particularly in urban and rural areas struggle financially to offer even the most basic level of education, when arts, music and sports programs are being cut because of lack of funding, and when politicians remain polarized over the role government plays in promoting quality education, institutions of higher education must step in.

In particular Freire sees universities in his native Brazil stepping in and providing teacher enrichment services for overworked and under-prepared teachers. In our U.S. context programs could be created to help community residents address local issues and challenges, as well as providing support and succor for movements for social change. For the past several years I have sought to bring my skills and experience to serve local neighborhoods and to be a support for efforts to enrich the quality of life in those places. I have offered my writing and analytical abilities to efforts of activist groups to address social inequities. Yet I have done these things largely without the knowledge or the support of my institution; i.e. it has been on “my own time.” I have often wondered what it would be like to have part of my responsibilities to share my research and teaching opportunities with these communities. What if my courses could involve students with local residents where both students and community folks could be educated by each other. I have done these things by taking my students to these places, but again it has often felt like I have done it in spite of rather than because of my responsibilities as a professor.

Many colleges would contend that they serve the community by the graduates they send into the workforce and the community at large, but Friere would say, and I would agree, that such a vision is far too narrow. In the midst of the current economic disparity, institutions of higher education have both the opportunity and the duty to seek to find ways to concretely and continuously engage with the communities around them and even beyond in the global community in ways that are enriching and life-giving for both. I, for one, would welcome that paradigm shift.