On May 5 Rev. David Brown, a diversity advisor at Temple University, and I held a public conversation focused on the major themes of my book Disrupting Whiteness. The event was sponsored by the Inside-Out Prison-Exchange program, which brings together traditional undergraduate college students and incarcerated men and women in a college course. Following the conversation, there were a number of questions raised, some of which we were able to address, but many because of time we were not. Over the next several weeks I would like to address these questions.

For those who would like to view the entire conversation, it can be found at https://www.facebook.com/theinsideoutcenter/videos/756890645187518

Question: How can we help white people see racism as more than just interpersonal, actions between individuals? Why is it so hard for white people to think in terms of institutional or systemic racism?

The Culture of Individualism

Most people who have grown up in the United States have been socialized to believe that their successes and failures in life are due to their individual efforts and intelligence. The idea of individual meritocracy is a central tenet of American culture. Thus, when Americans look around at other persons, they assume their station in life, their level of education, their wealth or poverty and other aspects of their lives are a result of that person’s individual effort, drive, intelligence and fortitude. This is as true for Black and Brown Americans as it is for whites. All too often they don’t realize or recognize the cultural, institutional and systemic factors that either made their paths easier or more difficult.

In the Introduction of Disrupting Whiteness I describe how I grew up in an upper-middle-class suburb of Minneapolis. I attended one of the highest-rated public high schools in the nation and had opportunities to work with and get to know professional people at all stages of my development. My dad was a businessman, my youth leader was a lawyer, my coaches were doctors and the parents of my friends were professionals. Upon graduation from high school, I attended Duke University, one of the most prestigious colleges in the country. As I wrote, I was led to believe “that my experience as a middle-class, white, heterosexual male [was] the same experience as that of all persons regardless of race, gender, class or sexual orientation” (p. xxi). I go onto say “I didn’t realize that the game was rigged in my favor.” What I mean by that statement is that the schools I attended, the jobs I worked, and the people I networked which set me up for success in ways that others without those advantages never had. Those advantages are what is often called white privilege and are supported by institutions and systems that serve whites in ways they did not and do not serve BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and other People of Color).

Because of our culture’s focus on individualism, white Americans also tend to think of racism in individual terms. Racism is thought of as ways of speaking and acting that are hurtful, disrespectful and degrading to individuals of other races. Thus, if white people do not want to be considered “racist,” they choose not to act or speak about people of other races in those ways. Likewise, they look at people who attack Asian-Americans on the street or police officers like Derek Chauvin who killed George Floyd as “racist,” who then need to be dealt with on an individual level.

Institutional and Systemic Racism

However, as I point out in the book, racism is not only interpersonal; it is also institutional and systemic. While not necessarily overtly intending to be discriminatory, the policy and practices of organizations and the laws governing systems like the public schools or the criminal justice often do in fact favor whites over BIPOC. When that happens, we have institutional racism. Thus, a person can participate in institutional or systemic racism simply by going along with those policies, practices and laws, and not raising questions about their discriminatory effects.

Institutional and systemic racism are most clearly seen in the impact of those policies and practices rather than their stated intent. Systemic and institutional racism becomes evident when we see the disparities in areas such as government spending for public schools, inequality in access to health care, or in the huge differences in the median wealth of Black and Brown families as compared to the median wealth of white families.

Helping Whites Understand and See Institutional Racism

In trying to help white people understand and see institutional racism, I try to share evidence of the disparities between whites and BIPOC in a particular area of life such as public school, funding, conviction rates based on race for similar crimes, or the huge disparities in people’s access to health care based on race. Then I ask them to consider why these disparities exist.

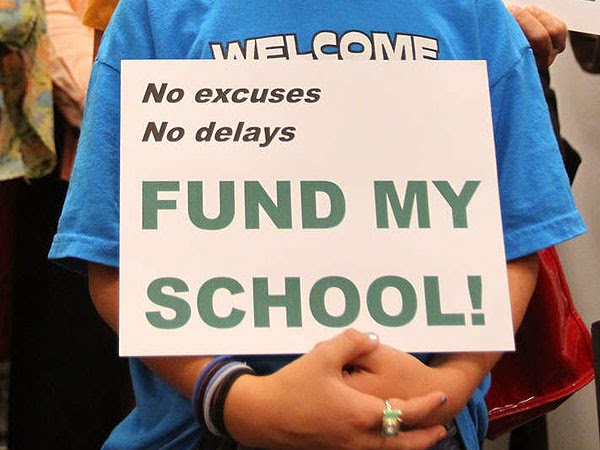

So, for instance, why does an African-American or Latinx student go to a local school with lead and asbestos in the walls, overcrowded classrooms and out-of-date books, while a suburban white student has a relatively new and clean building with up-to-date materials and manageable class sizes, when both schools are government-sponsored public schools? Why are the predominantly white schools so much better equipped than the predominantly Black and Brown schools? When we look at how much money each district invests per student, we see huge discrepancies in funding. Why is that? What is causing the disparity? The students in each school could be working equally hard, but the resources they have to work with are of vastly different quality and quantity. This is a sign of institutional racism.

One of the reasons it is so hard for people to see evidence of institutional and systemic racism is because they aren’t made aware of the discrepancies, and when they are it is often couched in language made to make the white students feel guilty. The white students in the well-funded school are not personally guilty for any wrongdoing, but they, and more importantly the administrators and legislators that facilitate those discrepancies, must be held responsible for eradicating the inequities to ensure quality education is available to all students regardless of where they live or the color of their skin.

I have sketchily outlined here how institutional racism operates in public education, something I have worked on for the last ten years. But the same kind of analysis could be run on access to healthcare, city services such as street cleaning and garbage pickup, sentencing in the courts, rates of pay and hiring and promotion practices in businesses.

Now because American whites are so deeply socialized into individual meritocracy, they will often try to come up with rationalizations for these discrepancies. Their sense of self-esteem is deeply rooted in what they as individuals have been able to achieve and accomplish, and the idea that the systems that shape their lives may have given them a head start can be very threatening. They may even accuse the questioner of reverse racism, that somehow talking about institutional racism means some of their “stuff” or position will be taken away. We need to stress that focusing on institutional and systemic inequities due to racism is about equity and fairness not reversing the order. It is about allowing everyone to run their race in life from the same starting line. Individual effort and creativity still matter. All we are asking for is giving every American regardless of their racial and ethnic background an equal shot at success and reaching their full potential. Challenging institutional and systemic racism does not seek to erase the importance of individual effort. Rather, it merely seeks to give every person, regardless of race or ethnicity access to the same resources and opportunities for growth and development.