In this posting, we continue our discussion of antiracism as spiritual formation by looking at the way the Christian faith, as it is often conceived and practiced, has been shaped and distorted by systemic and historic racism.

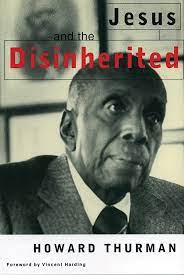

Howard Thurman in India

In 1935 when he was the chaplain of Howard University, the renowned theologian and mystic Howard Thurman led a six-month delegation of African American leaders on a pilgrimage to India. The highlight for Thurman was to meet and speak with Mahatma Gandhi. However, a major objective of the trip was to have interfaith dialogues with their Indian counterparts around their shared legacies of oppression. As a result, Thurman had several opportunities to speak with Hindu scholars about the struggles of African Americans in the United States.

In his book Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman describes how after delivering a speech at the Law College at the University of Colombo in Ceylon, he was invited to speak with the principal of the college. In the conversation the principal raised questions about Thurman’s Christian faith. He described how Thurman’s ancestors had been forcibly removed from their home in Africa, crammed into ships, and taken to the shores of North America. They were enslaved, whipped, and forced to work against their will. Even after slavery was legally abolished, they were segregated, lynched, and denied basic human rights by their white counterparts. He noted, “The men who bought slaves were Christians. Christian ministers, quoting the apostle Paul, gave sanction of religion to the system of slavery…. During all the period since then you have lived in a Christian nation in which you are segregated, lynched, and burned.”

In his book Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman describes how after delivering a speech at the Law College at the University of Colombo in Ceylon, he was invited to speak with the principal of the college. In the conversation the principal raised questions about Thurman’s Christian faith. He described how Thurman’s ancestors had been forcibly removed from their home in Africa, crammed into ships, and taken to the shores of North America. They were enslaved, whipped, and forced to work against their will. Even after slavery was legally abolished, they were segregated, lynched, and denied basic human rights by their white counterparts. He noted, “The men who bought slaves were Christians. Christian ministers, quoting the apostle Paul, gave sanction of religion to the system of slavery…. During all the period since then you have lived in a Christian nation in which you are segregated, lynched, and burned.”

Then the principal concluded, “I am a Hindu. I do not understand. Here you are in my country, standing deep within the Christian faith and traditions. I do not wish to seem rude to you. But sir, I think you are a traitor to all the darker peoples of the earth. I am wondering what you, an intelligent man, can say in defense of your position.”

Thurman’s response was to make a distinction between the Christianity the principal described and the faith Jesus taught and exemplified. He pointed out that he belonged to a small minority of Christians who believed God called for equality and that tragically the true message of Jesus has not been heard and even less lived out. He explained that for many African Americans, Christianity was a way out, contrary to the Christianity of subjugation preached by their enslavers. While Thurman acknowledged the ways in which Christianity was used to bless and justify the suffering of his ancestors, he claimed not to follow that faith, but rather the “religion of Jesus.”

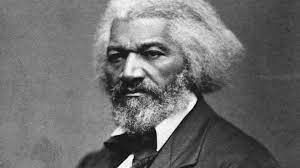

Frederick Douglass and a Slavemaster’s Faith

Frederick Douglass, the former slave who became a leading voice for the abolition of slavery, makes a similar distinction in his autobiography. He tells the story of his master, Thomas Auld, who became a Christian at a Methodist evangelistic meeting, and considered himself a devoted believer. Yet Douglass saw him tie up an enslaved woman and whip her bare shoulders until they bled. Based on observations like that, Douglass realized that there was “the widest possible difference” between the “slave-holding religion of this land and the pure, peaceable Christianity of Christ.” He noted, “For all the slaveholders I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst.”

While we would like to believe such harsh indictments of Christian cruelty and hypocrisy are a thing of the past, many historians would beg to differ. In her book, White Evangelical Racism, Anthea Butler demonstrates how throughout U.S. history evangelical Christianity has both been informed by and given sanction to racist practices and beliefs. She also notes that while the overt atrocities were being committed in the southern U.S., northern manufacturers quietly and passively used the cotton and other products from the south to build their wealth. Other authors, such as Mark Charles, have clearly documented the way Papal decrees in the 15th century, referred to as the Doctrine of Discovery, gave explorers like Columbus sanction to kill, enslave and overtake Indigenous peoples and their lands.

Christianity’s Racist Legacy

We who live today are the inheritors of this heritage and history and their consequences. Many of us who are white have inherited wealth that was gained at the expense of peoples of color whose basic needs and rights have been systematically denied, rights such as quality education, accessible healthcare, safe homes and surroundings, and the ability to earn a living wage. Our universities, banks, major corporations, and even churches have hidden legacies of exclusion, violence, and exploitation of BIPOC communities. We have tricked ourselves and each other into thinking that the era of brutal racism is past and therefore no longer relevant, when in fact the effects of the past confront us every day. We only need to look beneath the surface of our daily lives and honestly acknowledge the oppression and marginalization all around us. And if we are a person of color, every day we must face the reality that we live in a society and culture that regards us as less worthy, less capable, and in some cases less human.

These are the realities and forces we must contend with when we talk about spiritual formation from an antiracist perspective. We must reflect on the ways historic racism has infected and distorted the faith and practice that Jesus calls us to. Today there are many brands of religion that call themselves “Christian,” but are antithetical to the message and example of Jesus. For instance, there is the so-called “prosperity gospel” which teaches Jesus as the way to personal wealth. There is Christian nationalism that links a conservative political agenda to evangelical faith. There are Christians who characterize the narcissistic, self-absorbed, lying, twice-indicted former president as some sort of savior figure. While these expressions may go by the label of “Christian,” they are not reflective of the “religion of Jesus.”

Spiritual Formation

As I have stated before, we must come to terms with racism’s grip on understanding our faith and choose the way of Jesus that honors the dignity of all people and moves us toward justice for all. As Jesuit scholar Patrick Saint-Jean writes: “Being an antiracist requires persistent self-awareness, constant self-criticism, and regular self-examination.” We must reflect on ways we have absorbed the lies of racism  that are embedded in our beliefs which have influenced to be passive in the face of clear injustices. We must look beyond the surface of reality to the institutions and systemic forces that constrain us. We must admit the ways we have chosen to be silent for fear of pushback, rather than speaking up when microaggressions and other racist comments need to be confronted. We must commit ourselves to live out and follow the example of Jesus in how we relate to those around us and resist and overcome racism’s grip on our lives, our thinking, and the faith we claim to profess.

that are embedded in our beliefs which have influenced to be passive in the face of clear injustices. We must look beyond the surface of reality to the institutions and systemic forces that constrain us. We must admit the ways we have chosen to be silent for fear of pushback, rather than speaking up when microaggressions and other racist comments need to be confronted. We must commit ourselves to live out and follow the example of Jesus in how we relate to those around us and resist and overcome racism’s grip on our lives, our thinking, and the faith we claim to profess.

Such commitments are neither easy to make nor to fulfill. The capacity to stand up to racism in whatever form it appears must come from a deep inner strength and spiritual core. That is why spiritual formation is so central to an antiracist way of life. Spiritual formation is the process by which we get clarity on how we are to live and the fortitude to live in a way that decries injustice and works for a society and a world that reflects the open-armed, incredible love and grace of the man from Nazareth.

Sources

Butler, Anthea (2021). White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America. Chapel Hill, NC. University of North Carolina Press.

Charles, Mark & Rah, Soong-Chan. (2019). Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Dixie, Quinton & Eisenstaedt (2011). Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Non-violence. Boston: Beacon Press.

Saint-Jean, Patrick (2021). The Spiritual Work of Racial Justice. Vestal, NY: Anamchara Books.

Thurman, Howard (1949/1976). Jesus and the Disinherited. Boston: Beacon Books