In 2000 Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann published a series of essays under the title Deep Memory, Exuberant Hope. In one of those essays he suggests that the North American church iis experiencing a sense of dislocation in our increasingly post-Christian society. He identifies several signs of this dislocation including Christians being less certain what they believe, a decreased status of the church’s role in society, confusion about the nature of the Church’s mission, an increased mean-spiritedness about certain beliefs and norms, and the increase in financially-strapped congregations struggling to meet their basic bills. In such times of struggle and dislocation, individuals and groups are drawn to two general responses: denial or despair. Both responses, says Brueggemann “prevent any serious engagement of the crisis of dislocation into which we are not plunged.” (1)

If the Christian church was facing dislocation in the late 1990’s when Brueggemann wrote his essays, it is even more so 20 years later in our post 9/11 and post-recession era. Recent events have only served to heighten Christians’ sense of dislocation. A recent report by the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office documented over 1000 cases of child sexual abuse at the hands of 300 priests over the course of the last 70 years in the state; the youngest victim of this abuse was only 18 months old at the time of the incident. This is only a small percentage of the worldwide phenomenon of clergy sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic church. Pope Francis and the Roman Catholic hierarchy have been shaken and challenged to offer a response that can assure Roman Catholic faithful that the Church is not morally bankrupt to the core for not only allowing, but also covering up these horrific acts. And while the spotlight is on Roman Catholic leaders at this moment, we know that such atrocities are not limited to Roman Catholic clergy or just clergy, but include Protestant leaders, teachers, sports coaches and many more.

If the Christian church was facing dislocation in the late 1990’s when Brueggemann wrote his essays, it is even more so 20 years later in our post 9/11 and post-recession era. Recent events have only served to heighten Christians’ sense of dislocation. A recent report by the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office documented over 1000 cases of child sexual abuse at the hands of 300 priests over the course of the last 70 years in the state; the youngest victim of this abuse was only 18 months old at the time of the incident. This is only a small percentage of the worldwide phenomenon of clergy sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic church. Pope Francis and the Roman Catholic hierarchy have been shaken and challenged to offer a response that can assure Roman Catholic faithful that the Church is not morally bankrupt to the core for not only allowing, but also covering up these horrific acts. And while the spotlight is on Roman Catholic leaders at this moment, we know that such atrocities are not limited to Roman Catholic clergy or just clergy, but include Protestant leaders, teachers, sports coaches and many more.

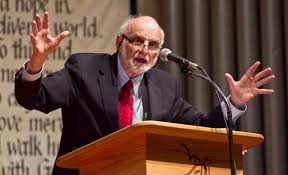

At the same time we have seen these terrible acts coming to light, equally troubling is the wholesale support of Evangelical leaders for the policies of Donald Trump. On August 27 the White House held a dinner for evangelical leaders, the purpose of which was to rally their support for the upcoming midterm elections particularly around Trump’s positions on restrictions on immigration, the limiting of refugees, abortion, and LGBT rights. These are positions held by an array of American voters, and the conservative wing of the Evangelical movement has been firmly and outspokenly supportive of the President and his “America First” policies. What is frightening is a similar relationship existed between the German Lutheran Church and Adolf Hitler. Hitler was able to justify his persecution and genocide against the Jews largely through silent support of the German Lutheran church. Dissenters like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Niemoller, both Lutheran clergy, sought to call this to light, all to no avail. In a similar manner, some evangelical leaders, like Shane Claiborne and Tony Campolo are calling out their evangelical brethren, but to date have been ignored (2).

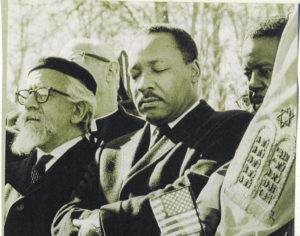

Now the progressive (non-evangelical Protestant) wing of the church has not been without its faults as well; this would be the group with which I most closely identify Too often we have been outspoken about what we are against, and not been clear of what we are for. In this blog, I can rightfully be accused of harping on the negative, rather than the vision of what we are for. Paulo Freire and Liberation Theologians talk about finding the balance between denunciation (challenging what we are againsts) and annunciation (proclaiming a vision of the new society we are for), and perhaps we have done too much of the former at the expense of the latter. Like the late Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. while we challenge the status quo, we must point people to an alternative as King did when he spoke of the Beloved community.

Brueggemann suggests that in such times of dislocation, the portion of Scripture that speaks most directly to our situation are those sections of the Hebrew Bible that speak about the period of the Exile. In 587 BCE the city of Jerusalem and the southern kingdom of Judah were overtaken and conquered by the Babylonian Empire (roughly equivalent to modern day Iraq). Over 100 years earlier the Northern Kingdom of Israel had suffered a similar fate at the hands of the Assyrian Empire (modern day Kurdistan). Thus in 587 BCE the Jewish people ceased to exist as a people. Not only that but the leading citizens of Judah – political leaders, educators, priest,s artists, and so on – were rounded up and deported thousands of miles away to cities across the empire. It would be more than 80 years later when returning exiles led by the likes of Nehemiah and Ezra would return to the land and begin to lead a rebuilding effort of the nation. That 80 year period is what is often referred to as the Exile.

In seeking to understand the reasons for the Exile, the Hebrew prophets like 2nd Isaiah, Jeremiah, Micah, Amos and Habakkuk often pointed to the fact that the Jewish believers had forsaken their commitment to the teachings and worship of their God, Yahweh. They pointed to two things in particular: idolatry (the worship of other gods) and mistreatment and injustice toward the poor in their midst. Reading through the writings of these prophets can be quite sobering as chapter after chapter, God thru the prophets vents his anger, disappointment and even hate for the errant ways of the God’s people.

Among many ways of dealing with the conditions of exile Brueggemann suggests that the people must let go of despair and denial and be honest about their unfaithfulness. This honesty often takes the form of  lamentation, a particular form of biblical speech which both recognizes one’s failures while reaffirming one’s trust in God’s ultimate care and goodness. Soong-Chan Rah in his book Prophetic Lament, says that “Lament recognizes the struggles of life and cries out for justice against existing injustices.The status quo is not to be celebrated but instead must be challenged.” (3). In those words we hear a call away from both despair and denial. For those who say the Church is lost, we are not to give in but challenge the church to do better. To those who want to deny the injustices in our world and in the church itself, we hear the call to challenge the status quo and call for greater honesty, fuller compassion, increased justice and genuine reconciliation.

lamentation, a particular form of biblical speech which both recognizes one’s failures while reaffirming one’s trust in God’s ultimate care and goodness. Soong-Chan Rah in his book Prophetic Lament, says that “Lament recognizes the struggles of life and cries out for justice against existing injustices.The status quo is not to be celebrated but instead must be challenged.” (3). In those words we hear a call away from both despair and denial. For those who say the Church is lost, we are not to give in but challenge the church to do better. To those who want to deny the injustices in our world and in the church itself, we hear the call to challenge the status quo and call for greater honesty, fuller compassion, increased justice and genuine reconciliation.

Personally I find Brueggemann’s description of our situation as exile to be both clarifying and sobering. In my own Anabaptist tradition, there is a clear conviction that the Christian community is to reflect the love, the compassion, the humility, the concern for the oppressed and other attributes of Jesus in the way we as followers of Jesus relate to one another and the world around us. We do these things in the first place not because we are Democrats, Republicans or Socialists, but because we are followers of Jesus. And when we disagree we don’t vilify and dismiss our fellow Christians, but seek to find a way to continue to struggle together for what it means in this era to be a follower of Jesus in our personal and public lives. In a real sense what Brueggemann reminds us of is that our charge is to seek to live out the Reign of God here and now, and to not let cultural and political differences so cloud our vision that we lose sight of the One we ultimately serve.

Now I will be the first to admit, I too often see the failures and blindness of those in the conservative wing of the Church with whom I disagree. I am reminded of Jesus’ admonition to take the log out of my own eye before criticizing the speck in another’s eye. (4) So I am admitting my own failure in this regard in the hopes that as followers of Jesus we can better relate to one another. Too often in secular culture the word “Christian” is synonymous with rigidity, judgmentalism, and hard-heartedness toward the “other.” We unfortunately have lived down to that depiction, and can only change perceptions as we change our interactions with each other and those who are “other” around us.

NOTES

- Walter Brueggemann, Deep Memory, Exuberant Hope, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2000.

- Shane Claiborne & Don Golden, “When Christians Sell out Christians for Political Power,” Religion News, 8/29/ 2018 Retrieved at https://religionnews.com/2018/08/29 /when-christians-sell-out-christians-for-political-power/ 1/9

- Soong-Chan Rah, Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015

- Matthew 7:3

Excellent assessment! Why I have not felt at home in most conventional churches. I DO feel at home in my Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Northfield however. Living our 7 principles help me feel like I am practising humanist principles like #1: The dignity and worth of every Being. I am more comfortable with the idea that in doing so, I AM following the teachings of Jesus as well. No blame. No shame. Just LOVE and compassion and respect for self AND others. We are all part of the same WEB of life. What we do to another,we do to ourselves. Golden Rule needs to be remembered again.

Kindest regards…..

Drick, Your hatred of all things Trump is really beneath you. To compare what is going on with Trump and his supporters to Nazism and Hitler is absolutely sinful on your part. You are an ordained minister and a professor and fine Christian man. It’s time you learn how to discuss the issues with respect and understanding for the other view. Period. I am an avid Trump supporter and I believe with all my heart in Jesus. I simply have a different world view than you do. Hitler! Shame on you.

Steve – In the spirit of this blog of trying to dialogue across differences, I am going to try and respond to your comment, but I will do it outside this blog