In my introduction to this series on “Antiracism as Spiritual Formation” I shared a definition of spiritual formation offered by Dr. Robert Mulholland in his book Invitation to a Journey: A Road Map for Spiritual Formation. In the preface to that book Mulholland offers what he calls a “simplistic definition of spiritual formation,” (p. 16) that highlights the essential nature of what it means to be a follower of Christ. He writes: “Spiritual formation is a process of being formed in the image of Christ for the sake of others” (p. 16). Over the course of this series on Antiracism as Spiritual Formation entails, I will explore all the fullness that definition, but I want to start with the phrase “being formed in the image of Christ.”

While to some it may seem to be an obscure theological point, I prefer to make a slight adjustment in Mulholland’s definition by saying we are being formed in the image of Jesus instead of Christ. “Christ” is a title given to Jesus in the gospels, indicating that he is the “anointed one,” the one Jews called the Messiah. As Jesus says in John 14, to know him is to know God. Jesus, the human expression of God, is the one we are called to follow and emulate. In other words, spiritual formation is the process of becoming like Jesus of Nazareth. Thus, I prefer to say spiritual formation is the process of being formed in the image of Jesus for the sake of others

Mulholland goes on to further explain what he means: “We are created to be compassionate persons whose relationships are characterized by love and forgiveness, persons whose lives are a healing, liberating, transforming touch of God’s grace upon our world” (p. 41). He stresses being formed in the image of Jesus is not just some sort of add-on to one’s life but rather is meant to be the essence who we are and how we move through the world. By referring to spiritual formation as a process, Mulholland admits that no one person can claim to have been fully formed in the image of Jesus, but rather we seek to reflect Jesus as “the fulfillment of the deepest hungers of the human heart for wholeness” (p. 42). As people of faith, we are on a journey whose destination is a life characterized by the actions, motivations and character of the carpenter from Nazareth.

My guess is that most, if not all persons who claim to be Christian, could generally affirm Mulholland’s definition of spiritual formation and the nature of the Christian life. However, when we drill down to specifics, we run into huge discrepancies. The history of Christianity in Europe and the United States is rife with acts of violence and destruction. The Doctrine of Discovery, first articulated by a Roman Catholic pope in 1493 (and actually written to U.S. court cases as recently as the early 2000s), was used to slaughter the indigenous residents of the North American continent, infect them with diseases and forcibly remove them from their ancestral lands. The drive to institute chattel slavery in the American colonies, and eventually the nation, justified the subhuman treatment of enslaved African peoples in the name of economic progress. This “peculiar institution “sought and received justification by Christian leaders who said such treatment was ordained by God. Following a Civil War in which both sides claimed to be fighting for God’s justice, Black codes, lynching, and segregation were reinforced regularly from Christian pulpits. And when the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum in the mid-1950s, it was mostly white Christian leaders who blessed the violent response against those advocating for equal rights.

These historic atrocities are often denied, ignored or diminished by many Christians. But these things done in the name of God, and supposedly in service to Jesus, have scarred and shaped our current understanding of who God is, and who God calls us to be. Our ignorance and denials of this past has only served to highlight our hypocrisy as followers of values and practices other than those of Jesus.

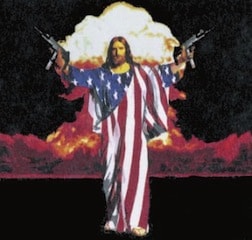

Today, among people who do not profess to be followers of Jesus, the label “Christian” is often associated with judgmentalism, exclusionism, and the denigration of those whose practices, identities, and politics do not align with a certain narrow-minded notion of righteousness. So-called Christians advocate for the free and full access to firearms, the banning of books that do not conform to a certain white, conservative standard, the passage of laws outlying abortion and a rigid rejection of desperate migrants seeking a new life in this nation. Christianity is seen as closely aligned with a brand of white nationalism that denigrates any individual or group that does not conform to their narrow standards. In fact during the January 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol, Christian flags were waved alongside ones bearing Nazi Swastikas, Stars and Stripes and the words “Don’t Tread on Me.” Furthermore, to many BIPOC observers, even those who might see themselves as Christians, this expression of their faith is not only cruel, it is outright racist in its tone, expression and intent.

politics do not align with a certain narrow-minded notion of righteousness. So-called Christians advocate for the free and full access to firearms, the banning of books that do not conform to a certain white, conservative standard, the passage of laws outlying abortion and a rigid rejection of desperate migrants seeking a new life in this nation. Christianity is seen as closely aligned with a brand of white nationalism that denigrates any individual or group that does not conform to their narrow standards. In fact during the January 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol, Christian flags were waved alongside ones bearing Nazi Swastikas, Stars and Stripes and the words “Don’t Tread on Me.” Furthermore, to many BIPOC observers, even those who might see themselves as Christians, this expression of their faith is not only cruel, it is outright racist in its tone, expression and intent.

While there are many, perhaps even a majority of professing Christians who do not align themselves with these heretical expressions of their faith, to many outside observers, anything having to do with Jesus carries the negative connotations mentioned in the previous paragraph. Moreover, all too often professing Christians practice their faith in a largely private manner and do not speak up or out against these distortions, Going back to Mulholland’s definition, all too often professing Christians do not see what they believe and how they act as “for the benefit of others,” outside of their immediate relational circles of family and friends.

In many ways it comes down to how we think about Jesus, who he was, what he stood for and the people with whom he most closely identified with. All too often we who call ourselves Christian, have fashioned a Jesus in our own image and the values and priorities of American culture. We end up with the Jesus of the NRA, the Jesus of capitalism and the Jesus wrapped in patriotism, rather than the Jesus we meet in the gospels, the Jesus who was the embodied depiction of God, the Jesus who aligned himself with the poor, the marginalized and the forgotten. Jesus did not come to fit into our small-minded way of life; rather he came so that we might seek to become more like him, and in so doing more like God desires us to be and do.

And so, as we seek to become like Jesus in our attitudes, values, and actions, we must examine who Jesus was in his place and time, and what kind of Jesus we have chosen to worship and follow. More on that in my next post.