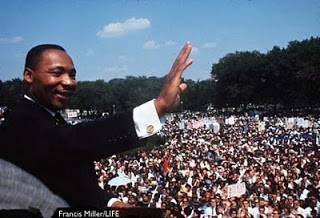

Each January we are invited to remember the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This weekend many folks will be engaged in service projects, special worship services and cultural events. This year I will be participating on the “Conversation of Kings: From Dream to Sacrifice Toward a More Perfect Union” sponsored by the New Conversations on Race and Ethnicity (NewCORE) in Philadelphia being held at Girard College (9 am) and South Philadelphia High School (1 pm). If you are around, come join us.

For me the Martin Luther King holiday is a day to remember the history of racism and to reflect on my efforts to overcome the effects of that racism in our nation and in my own personal life. For that reason I was particularly intrigued by a recent column by Leonard Pitts, Jr, “Don’t Let Others Define Us.” In this article Pitts writes of a trip he once took to Auschwitz, the Nazi prison camp where thousands of Jews were killed during World War II. During his time there, he was surprised to learn that Israeli school groups regularly visit the site to continually remind the next generations of the genocide that killed six million of their fellow Jews. Pitts wrote that he was “impressed with the way Jews have institutionalized Holocaust education.” By contrast he says that generally speaking African Americans tend to distance themselves from their past of suffering. He quotes one woman who witnessed a lynching in 1930, and who refused to talk about it with anyone and countered by saying “Why bring it up. It’s not helping anything. People don’t want to hear it.”

The point that Pitts makes is that if a people does not work hard to remember their history and allow it to shape and guide their actions in the present, others who have a vested interest in sanitizing the ugliness of their past will do it for them. I think this tendency to sanitize the ugliness of history is powerfully at work in our remembrance of Martin Luther King, Jr. This is true not only of African Americans, but also most certainly among White Americans as well. These days people like to quote a few choice lines from the “I Have A Dream” speech without focusing on King’s advocacy for the poor, his opposition to militarism, and his continual battle with local governments to change laws that treated African Americans as less than human. We forget that the FBI spied on him and spread lies about him, and that only when the brutality of racism was dragged onto the world stage did the Federal government begin acting to change discriminatory laws and practices that had been institutionalized for centuries. We forget that King and his followers were beaten and regarded as communist subversives, and that King himself was assassinated as he was participating in a strike by underpaid garbage workers in Memphis.

We also forget that while there was virulent minority of whites who participated in violent acts of racial hatred and intimidation, and a activist minority of whites who publicly allied themselves with the Civil Rights Movement, there was a much larger percentage of whites who sat on the side and did nothing. King’s famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” written while he was in jail was written to this “silent majority. While in jail King had being criticized by “white moderates” for not being patient and creating a social disturbance. They said that he should be patient and trust that prayer and time would bring about racial reconciliation. King responded at length to these charges and said that such an attitude was exactly why the racial injustices were allowed to continue. Of those who sat on the sidelines and preached patience, King wrote the following:

“I have reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice, who prefers a negative peace, which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

What King was saying then, still resonates today, that in matters of equality and social justice, there can be no fence sitters. To step aside and to not act is to reinforce the unjust status quo.

I would hope that on this Martin Luther King, Jr. day that both African Americans and White Americans would take time to reflect on the ugliness of our racist past, not so whites can feel shame and guilt and African Americans can feel anger and disgust, but so we can learn from, and hopefully not repeat, the same actions today. When I listen to how the immigration debate is framed, or why the Dream Act has not been passed, or how my fellow citizens treat Muslim-American with disgust and suspicion, I fear we have not learned from the past. The actions, words and rationalizations for our anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim attitudes are hauntingly similar to the actions, words and rationalizations used to deny basic civil rights to African Americans 60 years ago.

Leonard Pitts, Jr. asks his fellow African-Americans to remember their past and teach it to the next generation. I would ask White Americans to do the same. Just as a doctor can not provide a healing solution without uncovering the underlying disease, so too we can never reach King’s dream of racial justice and reconciliation without continually coming to grips with the racist past that brought us to this moment, and hinder our efforts to overcome the racial brokenness that afflicts us.

*** For those in the Philadelphia area, one place one might start to come to grips with that past is the Lest We Forget Black Holocaust Museum of Slavery in the Port Richmond section of the city. This private museum was put together by the descendants of former slaves and graphically illustrates what slavery, Jim Crow and institutional racism was and still is, and how history lives on in our interactions today as whites and people of color. I have taken several student groups there, and it has had a powerful effect on everyone.