Several years ago my good friend Mary Wade introduced me to the writings of Howard Thurman. Mary is an expert on Dr. Howard Thurman, having earned her PhD (1) after a long career with the American Friends Service Committee as well as serving as a Baptist pastor. Now in her 80s, Mary not only continues to teach about Thurman but also embodies the spirit and values he sought to convey throughout his life. In so doing she has inspired me to seek to know this man who has so shaped her thinking and action.

Howard Thurman was born in 1899 in Daytona Beach, Florida and despite fighting the barriers of racism throughout his life, he rose to be one of the most prominent 20th-century voices for the integration of spirituality and racial justice. While he was not overtly active in the marches and actions of the Civil Rights Movement, he was a pastor, mentor and spiritual guide to many of those on the forefront of the movement for human rights and racial justice, including the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

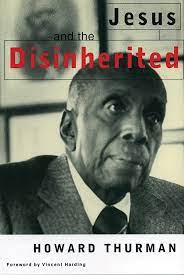

By the time Thurman died in 1981, he had delivered hundreds, if not thousands, of sermons and lectures, as well as written numerous books and articles. Thurman’s best-known book and the first one I read is entitled Jesus and the Disinherited published in 1949. Reading this book began a process that continues to this day in which my perspective and understanding of Jesus and his significance in his time and ours has been turned upside down.

In the Preface to Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman raises two questions: “Why is it that Christianity seems impotent to deal radically, and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination, and injustice on the basis of race, religion and national origin? Is this impotency due to a betrayal of the genius of the religion, or is it due to a basic weakness in the religion itself” Thurman believed that the answer to these questions lay in how Christians, especially in the mid-20th century United States, viewed and understood the central figure of their faith, Jesus of Nazareth. In the book he sets out to “examine the religion of Jesus against the background of his own age and people, and to inquire into the content of his teaching with reference to the disinherited and underprivileged” (p. 15).

He begins by highlighting three incontrovertible facts about Jesus. First, he says Jesus was a Jew. Throughout his life, Jesus sought to live out and embody the values of the teachings of his people, the Jews. Second, Thurman asserts, Jesus was a poor Jew. He was born among those masses of people who are born into situations of constant need and struggle just to survive. Third, Thurman states “Jesus was a member of a minority group in the midst of a larger dominant and controlling group” (p. 18), namely the Roman Empire.

When I first read the book, I saw Thurman’s insights to be academically interesting, but I must admit I did not comprehend their profound nature for several years. I did not fully grasp that Thurman was making a radical and powerful point: Jesus was an impoverished member of an oppressed people who came first and foremost to provide guidance and hope to his fellow impoverished and oppressed people. He was not a charismatic outsider coming to “rescue” the poor, he was oppressed and impoverished just like them.

In so doing Thurman makes a significant theological and spiritual assertion: Jesus did not come to prop up the status quo but came with a radical and prophetic mission to challenge the powerful and those who would use the Christian religion as a club to demean, oppress and exclude those who are poor, BIPOC and economically struggling. In other words, Jesus did not come primarily to save the upper-middle-class white folks like me but rather to challenge us to let go of our privilege and power, and to follow Jesus into the places of struggle, suffering and injustice.

Two decades later liberation theologians would call this posture “God’s preferential option for the poor.” However, what Thurman was in essence saying that from the time he was born, Jesus, the poor, oppressed Jewish carpenter from Nazareth was God’s preferential option for the poor throughout the world. I came to realize Jesus does not fit into my comfortable privileged life but rather calls me to stand with him as united with the oppressed. I was being called to understand and practice my faith from the perspective of those who are forgotten, marginalized, oppressed and (to use Thurman’s word) disinherited. This perspective includes those who are crushed, deprived, maligned and battered by the evils of racism.

If as I have been saying, spiritual formation involves being formed in the image of Jesus for the sake of others, then my faith must make resisting and overcoming the forces of racial oppression a priority. If Jesus came into this world to stand and fight with those at the bottom of society’s gutter, that is where I must seek to be and work. While this is much easier to say than do, this is the call that we must choose to follow. I have no illusions that I have fulfilled this call, but I believe all who call Jesus the center of their faith, this is the path we are called to follow.

The title of Mary’s dissertation is entitled Spirituality and Conflict Resolution: A Study of their Life and Teachings of Dr. Howard Thurman (