During this week of August 9-15 I have been travelling through southern Ohio studying the pre-Civil War anti-slavery movement and the Underground Railroad (UGRR). This trip was prompted by a small note in my family history I had found, which indicated that two of my ancestors, William Silver (1798-1881) and his son Albert R. Silver (1823-1900) of Salem, Ohio, were involved in the anti-slavery movement and most likely allowed fugitives from slavery to stay hidden in their homes enroute to freedom in Canada. I went on this trip to try and get a feel for what it would have been like for them and for others involved in the anti-slavery cause. As such I set out to learn as much as I could about the anti-slavery movement in Salem and throughout Ohio, to learn about what fugitives from slavery had to go through to find their freedom, and the routes they took through Ohio.

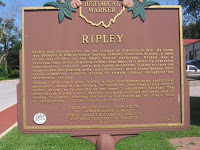

In the course of this week, I learned about the little town of Ripley, Ohio, a town on the banks of the Ohio River, which was a major entry point for fugitives escaping from Kentucky into Ohio. I went to Ripley to learn about two of their citizens, Rev. John Rankin and John Parker. After visiting their homes, learning more about their stories, and walking the streets of Ripley. I wrote the following reflection on why I had come to this little river town.

After visiting the home of Rev. John Rankin, abolitionist, leader of the UGRR, and a Presbyterian minister, I realized why I am on this trip; I am in search of social justice heroes, mentors and models from history. Rankin is such a man. As a “station chief” in the UGRR, he provided shelter and guidance to over 2000 fugitives (I can no longer call them “runaway slaves” after this trip) from 1821 to 1865. He did so publicly through his sermons and writings, especially “Letters on American Slavery” published and distributed in 1826. He did so covertly and illegally thru his leadership role with the UGRR. He was an activist and a public intellectual, a man of faith and political conviction.

He did so at the expense of his career; he was driven from a church in his native Tennessee; and he did so despite having a wife and 13 children. He did not use his family as an excuse for inaction and “playing it safe.” He did so at the threat of his life; “Wanted” signs in Kentucky offered a reward for his death.

In a search for mentors, we need to realize that seldom do they operate alone, even though we will put them on a pedestal; I don’t want to do that.For every Rankin, there was a congregation and host of others that supported him, cooperated with his efforts, and followed his leadership. He was able to operate as he did in Ripley because the people of Ripley shared his convictions and commitment to action.

Rankin was white, and one thing I have learned is that the commitment and conviction was far greater and deeper among blacks, both slave and free, than most whites, even those of Rankin’s character. For every John Rankin, there were also several John Parkers. Parker was a former slave who came to live in Ripley after he purchased his own freedom and moved from Alabama. He ran an iron foundry and had two patents. Parker was a “conductor” of the UGRR, meaning he ferried people across the Ohio River from the shore of the slave state of Kentucky to freedom in Ripley. Parker also had a family, and yet did not shrink from action. Despite numerous threats to Rankin, the danger to Parker was much greater – first because he was black and second because he was not a religious or a public figure. The culture being what it was then as now, Parker’s punishment would have been much greater than Rankin’s; the difference between then and now, in pre-Civil War America the Fugitive Slave Law clearly stated greater penalties for blacks, rather than being covertly rationalized as they are today.

This trip has given me new insights into what it takes for people of all faiths, colors and backgrounds to work for and achieve social justice. We all play our part.I cannot be a John Parker, but I can be inspired by John Rankin. I am blessed to be in the privileged position to be a servant of social justice; may I learn from John Rankin and not squander the opportunity.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful piece of history!