Jamaica Plain

In May 1975 after I graduated from Duke University, I packed up my 1968 Ford Mustang and headed north from Durham, NC to Boston, MA. I had gotten a summer job with a national Christian organization called Young Life. My job was to research the possibility of starting a new youth program in a neighborhood in southwest Boston called Jamaica Plain. I went there primarily because I wanted to work under a man named Dean Borgman, who I learned about in reading the book Tough Love (the first book I wrote about in this series). For much of my time there, Dean was my supervisor and was a great friend and mentor. Needless to say, I found there was fertile ground for a new program, and so those three months in Jamaica Plain ended up turning into four years plus another two years where I lived outside the community but still worked there.

In May 1975 after I graduated from Duke University, I packed up my 1968 Ford Mustang and headed north from Durham, NC to Boston, MA. I had gotten a summer job with a national Christian organization called Young Life. My job was to research the possibility of starting a new youth program in a neighborhood in southwest Boston called Jamaica Plain. I went there primarily because I wanted to work under a man named Dean Borgman, who I learned about in reading the book Tough Love (the first book I wrote about in this series). For much of my time there, Dean was my supervisor and was a great friend and mentor. Needless to say, I found there was fertile ground for a new program, and so those three months in Jamaica Plain ended up turning into four years plus another two years where I lived outside the community but still worked there.

My years in Jamaica Plain were transformative in numerous ways. It was my first job after college where for the first time I lived on my own. I learned how to cook, live on a very limited income, and establish myself in a neighborhood. I made meaningful friendships, some which last to this day. While there, I was mugged, had my house broken into, and had my car stolen. I found, like my neighbors, I could carry on despite those struggles. It was the first time I had lived in a low-income community. Just two blocks from my house was a housing project for low-income people. It was also the first time I had lived in a community where I was a racial and ethnic minority. While there were white families in the community, mostly Irish Catholic, the community was mostly composed of African-American and Puerto Rican families, with some Cubans and Dominicans in the mix. And it was the first time I witnessed injustice up close and personal.

The Busing Crisis

Motorcycle police escort school buses as they leave South Boston High Schoo

One year before I arrived in Boston (1974), Judge Arthur Garrity had ordered that the highly segregated Boston Public Schools be desegregated through forced busing. When I arrived in May 1975, the first year of that experiment was almost over. During the summer between the first and second year of busing (my first summer there), the tensions that had built up over the year exploded. Blacks were being beaten up in all white South Boston, white people were being dragged from their cars in all black Roxbury, and fires and violence were all around the city. In my neighborhood, one weekend police barricades went up so that I had to go past a police checkpoint just to get to my apartment.

What was odd to me was that of all the communities in Boston, Jamaica Plain was one of the most racially balanced. Yet the Black kids were bussed to one neighborhood across town, the white kids to another, and the Puerto Ricans went to the local high school, Jamaica Plain High School (JPHS). It made no sense, why did the kids in my neighborhood have to be bussed, when they could be integrated just staying close to home and go to JPHS? Meanwhile, the students in all-white, upper-middle-class West Roxbury didn’t get bussed anywhere, nor did any kids get bussed in. Why was West Roxbury not involved in bussing? This was only one of the numerous instances, where being white and wealthy afforded all sorts of privileges and exemptions the rest of the city did not enjoy.

Overt Racism

Of all the places I have lived (Minnesota: Durham, NC, Boston, MA; Jersey City, NJ; Philadelphia, PA), Boston was the most overtly racist. That is not saying there was no racism in those other places, for there certainly was, but Boston in 1975 was in-your-face racism. One summer I coached an all-black team in a summer basketball league. We joined the league because it was the closest to our community. However, when we walked up the hill, we entered a world of hostility we had not counted on. It turned out we were the only black team in the league. Very quickly I realized, as did my players, that the cards were stacked against us. The referees were so blatantly unfair toward us that I had to counsel my players to do their best to keep their cool and let me do the screaming and yelling. To say the least, I was not much appreciated in that league, and so the next summer we drove across town to an all-black league.

Of all the places I have lived (Minnesota: Durham, NC, Boston, MA; Jersey City, NJ; Philadelphia, PA), Boston was the most overtly racist. That is not saying there was no racism in those other places, for there certainly was, but Boston in 1975 was in-your-face racism. One summer I coached an all-black team in a summer basketball league. We joined the league because it was the closest to our community. However, when we walked up the hill, we entered a world of hostility we had not counted on. It turned out we were the only black team in the league. Very quickly I realized, as did my players, that the cards were stacked against us. The referees were so blatantly unfair toward us that I had to counsel my players to do their best to keep their cool and let me do the screaming and yelling. To say the least, I was not much appreciated in that league, and so the next summer we drove across town to an all-black league.

A Theology of Liberation

Fr. Gustavo Gutierrez

These were the kind of regular experiences that shaped my time in Jamaica Plain. In the midst of this time, I picked up A Theology of Liberation by Gustavo Gutierrez. Published into English in 1973, this book got me thinking in new ways about God and my faith in Jesus. As I have stated before, I grew up in an upper-middle-class community outside Minneapolis and participated in my local Young Life club, a Christian para-church program for high school; students. I had volunteered for Young Life while in college, and so it was a natural step to go on staff upon graduation from college. While I did not know the word “evangelical” at that time, Young Life was, and still is, an organization primarily focused on evangelizing young people to “accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior.”

Ostensibly, that is what I was in Jamaica Plain to do, but in the process I soon found that before I could talk about Jesus, I had to do other things. I was helping kids get food for their families. I was standing up with them against racist referees. I was counseling them about family problems. I was trying to assure them in the face of struggles with trying to find jobs instead of dealing drugs for some income. I was going to court with them and advocating on their behalf. I was insisting that if kids wanted to participate in our program, they were going to have to find ways to get along with kids of other races. Accepting Jesus was not relevant to kids and their families who were just trying to survive on the streets.

Gutierrez helped me come to grips with my dilemma. Gutierrez is originally from Peru, although for many years he has split his time between Peru and the University of Notre Dame. As a young priest, he found himself ministering to rural people living on the edge of existence. Revolutionary groups were springing up across Latin America in opposition to the powerful, landed elites that controlled most of the governments in Latin America (with the expressed help of the U.S. government). The Roman Catholic hierarchy seemed more interested in catering to the wealthy and powerful, rather than the poor. So Gutierrez, as well as many other priests across Latin America, began to rethink their theology. Out of their interaction with the poor and their theological reflections, liberation theology was born.

Gutierrez posed the problem this way:

“What relation is there between salvation and the historical process? … We are dealing with the classic question of the relation between faith and human existence, between faith and social reality, between faith and political action, or in other words the Kingdom of God and the building up of the world.

The answer Gutierrez came to was simply that salvation and liberation were in essence two sides of the same coin. One could not talk about a relationship with God and just focus just on eternal life, one also had to be concerned about the suffering and struggle of the poor in this life. To do less than that was to deny Jesus’ command to love one’s neighbor. Love for the neighbor who was poor and oppressed compelled one to join them in their struggle for fair wages, a fair court system, and governments that served the masses of people rather than the desires of the wealthy few. Gutierrez articulated this view in the simple phrase: “God’s preferential option for the poor.”

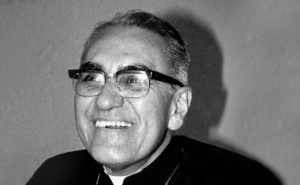

Gutierrez was not the first or the only to articulate such thoughts, but his was the first book published in English. And when the Western powers, particularly the United States, learned of this new movement, they accused them of being violent Communist revolutionaries. Some were, but most were non-violent. The Roman Catholic church defrocked or silenced some of the priests. Some were killed. Archbishop Oscar Romero [in the picture on left], the head of the Catholic church in El Salvador, was assassinated by the government troops while serving mass. Hundreds of the priests, nuns and regular parishioners also ended up being murdered or exiled across Latin America. Somehow Gutierrez survived.

Gutierrez was not the first or the only to articulate such thoughts, but his was the first book published in English. And when the Western powers, particularly the United States, learned of this new movement, they accused them of being violent Communist revolutionaries. Some were, but most were non-violent. The Roman Catholic church defrocked or silenced some of the priests. Some were killed. Archbishop Oscar Romero [in the picture on left], the head of the Catholic church in El Salvador, was assassinated by the government troops while serving mass. Hundreds of the priests, nuns and regular parishioners also ended up being murdered or exiled across Latin America. Somehow Gutierrez survived.

My Initial Embrace

I did not become fully aware of the situation in Latin America, and America’s complicity in the oppression until several years later. I also was not fully versed in the theological issues involved in the dispute between the priests and the Roman Catholic hierarchy. However, I implicitly connected to Gutierrez’s perspective that salvation, as I had learned about it, needed to be broadened to encompass all of life, and that following Jesus inevitably led one to fight for the basic needs of all people who are denied them.

Not long after reading A Theology of Liberation, I read Black Theology and Black Power by James Cone, published around the same time, which looked at liberation theology through the lens of America’s historic and systemic racism. Like with Gutierrez, I did not initially understand all the political, historic and theological intricacies of Cone’s position, but I had seen racism’s ugly face up close and personal, and it was clear to me as a Christian, as a follower of Jesus that one could not allow poverty, racism and other forms of oppression to go unchallenged.

While it was a long time before I came to fully understand and embrace liberation theology, Gutierrez and Cone started me on a lifelong process to embrace the words of Jesus in Luke 4 as a call to all followers of Jesus:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight to the blind

To release the oppressed

To proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

Years of study and reflection has led me to understand these words, as not just to do good works of charity for the poor, but rather to restructure society so that all people regardless of race, social position, economic status can live a full and free life.

Since reading A Theology of Liberation, I have read liberation theology in many forms; feminist, womanist, queer, African, Latinx, Native American, Palestinian, and other liberation theologies now populate the theological landscape. While they all have their unique dimensions, the things that hold them together is a recognition of suffering due to systemic injustice and God’s preferential option for the poor and oppressed.

Liberation Theology Today

Rev. William Barber

Liberation theology had its heyday in the 1970s, ’80s and early ’90s. In Latin America, Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism have taken hold establishing a more conservative option to liberation theology. Yet I find in these days of global capitalism, rampant nationalism and resurgent white supremacy, liberation theology has great relevance. In a later book, We Drink from Our Own Wells (published in English in 1980), Gutierrez writes “… poverty means death. It means death due to hunger and sickness or to repressive methods used by those who see their privileged position being endangered by any effort to liberate the oppressed.” To be poor is to face death daily and to experience death earlier.

I see the signs of death all around me due to inadequate healthcare, lead and asbestos in homes and school buildings, hopelessness turned to violence, mass shootings in all sorts of public places, inadequate wages and much more. As the wealthy elite celebrate a “growing” economy, a rising stock market, and burgeoning executive salaries, the reality of poverty contributing to early death is all around. This very week the Poor People’s Campaign under the leadership of Rev. William Barber has called attention to inattention of political leaders to the needs of the poor, and challenged presidential candidates to talk about their plans to address poverty in their platforms and debates. The disparity between the wealthy elite and the growing numbers of impoverished people only continues to grow and yet the wealthy ask for more. And not only here in the U.S. but in the streets of Hong Kong, the deserts of Yemen, the streets of Sudan, townships around Johannesburg and countless other unknown and unnamed places where people are demanding a change. This is liberation theology in action.

Just like when Gutierrez first encountered the Peruvian peasants, God’s preferential option for the poor and the call to join the struggle for justice and liberation is starkly clear. We are called to follow Jesus to the margins of society and give our resources, our energy, our very lives to work for justice and liberation.