This Martin Luther King Jr Day remembrance, at the urging of anti-racist activist

Ewuare Osayande I have re-read portions of Dr. King’s 1967 book,

Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community. Written two years after Selma and the signing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, King bemoans how little has changed since the law was passed because its provisions have not been implemented and its restrictions on discrimination have not been enforced. King also notes that many of the white allies who marched with him in Selma have retreated to their lives, treating that historic event as an experience rather than an historical watershed and a turning point in history. Overtly racist whites have struck back, segregationists have been elected to office, and violence against people of color continues. The words of 49 years ago sound hauntingly contemporary.

For King in 1967, as it is for many people of color in 2016, true equality remains a distant illusion. In the first chapter of Where Do We Go From Here, King writes:

Why is equality do assiduously avoided? Why does white America delude itself, and how does it rationalize the evil it retains?

The majority of white Americans consider themselves committed to justice for the Negro. They believe American society is essentially hospitable to fair play and to steady growth toward a middle class utopia embodying racial harmony. But unfortunately this is a fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity. Overwhelmingly America is still struggling with irresolution and contradictions. It has been sincere and even ardent in welcoming change. But too quickly apathy and disinterest rise to the surface when the next logical steps are to be taken. (p. 567)*

I wrote my book White Allies in the Struggle for Racial Justice to provide role models for white folks

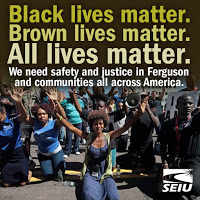

who say they are serious about seeking racial justice. The book provides stories of 18 white folks through U.S. history who lived their lives with racial justice as a central focus. What became so clear as I researched and wrote the book is that for white folks working for racial justice means moving out of our comfort zones and living against the grain of white culture. Noel Ignatiev calls such action being a “race traitor” and Tim Wise calls it “racial treason.” Whites may be uncomfortable with phrases like “Black Lives Matter” wanting to respond “Wait, don’t all lives matter.” However, when whites make such statements they ignore the fact that in terms of employment poverty, education, health care, criminal justice and so many other aspects of our society black lives matter far less than that of whites. The promises and accomplishments of the Civil Rights movement that had not been fulfilled in 1967, remain largely unrealized in 2016. Whites must affirm the slogan not because it suggests white lives don’t matter, but that in U.S. society today black lives are literally and figuratively left to die on streets all over the country.

King writes: “Like life, racial understanding is not something we find but something we must create.” (p. 572). On this MLK Day, whites must realize that if we desire a world where all lives actuall do matter, we will have to let go of our comfortable distance, perhaps face the anger and frustration of our colleagues of color, and commit ourselves to the long haul of racial justice.

When I talk about our call to work for racial justice, some white folks say: “I don’t want to do or say the wrong thing. How do I avoid a mis-step?” I respond by saying: “Get over it. Accept that you will mess up.” Working for racial justice is a messy, complicated, emotional, confusing process, but if you are in that process, mistakes can be overcome and forgiven. However, if we never step out of our comfort zone, we will make the greatest mistake of all: passively affirming the status quo.

[References to Where Do We Go From Here are from A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. Edited by James M.Washington]

Related