The Inside Out Program

Last week ( April 1-7) I participated in a teacher training conducted by the Inside Out Prison Exchange Program. Started in 1997 by Temple University professor Lori Pompa, Inside Out “facilitates dialogue and education across profound social differences. Inside Out courses bring traditional college students and incarcerated students together in jails and prisons for semester-long learning.” After two years of planning and preparation, the program started when a group of students from Temple University participated in a class with Lori that also included inmates from one of the Philadelphia prisons. To date Inside Out has trained over 900 teachers involving over 30,000 students – inside and out – operating in 45 states and several foreign countries.

Thirteen of us, mostly college faculty, joined with an equal number of men incarcerated at SCI Phoenix, a maximum-security prison 30 miles north of Philadelphia. The “inside” students were all alumni of the Inside Out program and had formed a “think tank” that meets regularly and provides programs inside the prison and facilitates training for “outside students” like the thirteen of us who have travelled from as far away as California to be there. For three whole days we participated together in a collaborative, dialogue-based experience of teaching and learning. While at night those of us who were outsiders were able to go home, and the inside students when back to their blocks, a bond of friendship was formed that will stay with us for a long time.

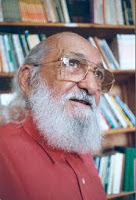

While Lori Pompa was not familiar with the pedagogical philosophy of Paulo Freire when she started the program, she states that the Inside-Out methodology is very much in line with Freire’s approach to teaching and learning. Freire consistently referred to his pedagogy as a “philosophy” rather than a “method,” because he insisted his principles of teaching and learning needed to be adapted to its immediate concrete context. So it isn’t that the Inside-Out approach has in some way copied Freire; rather it is an adaptation of his principles to the incarceration context. As one who has studied Freire deeply, published articles, made presentations, and written book on Freire, I found the Inside Out experience to be an opportunity to experience firsthand Freire’s philosophy in action.

Freire and Inside Out

While I hope at a later time to share my thoughts in more depth, let me share briefly some similarities that I see between Freire and Inside Out.

In his classic text , Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire spends a whole chapter debunking what he called the “banking method” of education, where one “expert’ – the faculty member – imparts knowledge into the “empty minds” of the students. This unfortunately is the dominant method of teaching that occurs in all levels of education from kindergarten all the way thru graduate studies. In its place Freire proposes what he call a “problem-posing” approach, that begins with where students are and what they know, and invites them into a process of dialogue around a particular subject or topic. Through various small group and large group exercises, the inside folks led us outside folks through a series of dialogues around a wide range of topics, and together we shared our insights around readings and various subjects in a way that was intellectually stimulating and emotionally bonding.

In his classic text , Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire spends a whole chapter debunking what he called the “banking method” of education, where one “expert’ – the faculty member – imparts knowledge into the “empty minds” of the students. This unfortunately is the dominant method of teaching that occurs in all levels of education from kindergarten all the way thru graduate studies. In its place Freire proposes what he call a “problem-posing” approach, that begins with where students are and what they know, and invites them into a process of dialogue around a particular subject or topic. Through various small group and large group exercises, the inside folks led us outside folks through a series of dialogues around a wide range of topics, and together we shared our insights around readings and various subjects in a way that was intellectually stimulating and emotionally bonding.

This process of dialogue is central to Freire’s approach to teaching and learning. Instead of having a hierarchy in the classroom, where one individual holds all the power, he calls teachers to be teacher-learners and students to be learner-teachers. In other words, the teacher seeks to position him/herself alongside students rather than over them and opens him/herself to learn from the students, even as he/she shares insights from his/her study and experience. Thus the dialogue is not coerced or manipulated, but is instead an authentic sharing of equals. While society places a much higher value on those outside prison walls, during our week with Inside Out we professors experienced a free and equal exchange with those whom society has shut away and treated as animals. The inside students were clearly identifiable by their prison uniforms, but beyond that it was a gathering of fellow learners and teachers that was freeing and inspiring.

One of the things Freire said was essential for effective dialogue is love, and there was great deal of love around the circles we formed, so much so that we became a learning community, rather than simply a collection of learning individuals. Freire believed that learning was a social enterprise and that by pitting students against one another in a classroom, the teacher creates an unhealthy individualism where there is little to no collaboration and sharing of knowledge, only competition. By contrast in our Inside Out training we continually sat in circles and worked in groups, so that as we worked together, we formed bonds that allowed our learning to go much deeper.

In his native Brazil Freire is best known for developing a method of teaching illiterate campesinos how to read in 40 days. One of the keys to his success was the fact that the words he used to teach folks how to read came out of their daily experience. This experienced-based approach to learning helped his learners to see the connections between what they were reading and their daily lives. In a similar way, Inside Out calls upon students to draw and learn from their experience as they consider various academic topics. Like Freire, Inside Out assumes that every person in the room has something to offer the others and thus encourages all to share those insights.

In addition to his critique of the banking method, the other concept that Freire is known for is what is called conscientization or as it is in Portuguese conscientizacao, which roughly translated means “consciousness raising.” However, in American classrooms conscientization is often wrongly taken to refer to an individual coming to some greater awareness of him/herself and the world around him/her. This is very far from what Freire means by the word, in fact after spending time in Western countries, he gave up using the word because it was so grossly misunderstood. For Freire conscientization is (1) something that happens to a group of people not just an individual, and (2) seeks to address a pressing challenge or problem in their community that (3) leads to concrete action to change an injustice in the community. Conscientization is about effecting social change through a cyclical and ongoing process of reflection-leading-to-action and reflection-on-action he called “praxis.”

During our dialogues with our Inside facilitators we addressed issues such as racism, power and privilege and the dehumanizing process of mass ncarceration in the U.S. today. We talked about the severe limitations placed on those on the inside of prisons as well as seeking to help from the outside. At the same time we saw that sharing and struggling together made us stronger, nd more committed to do all we can to change and/or deconstruct the current criminal justice system and to join those we know on the inside to construct lives of meaning, hope and purpose despite their dehumanizing context.

Transformation

A word that was used a lot throughout the week was “transformation,” and indeed for me the week was transformative. It was transformative first and foremost because of the people I met on the inside whom society has labeled as “criminals,” “degenerate” and unredeemable, yet who I found to be caring, intelligent, thoughtful individuals. It was also was transformative because I got to see what Freire’s pedagogical philosophy looks like in a prison. I can imagine had he been with us last week, Paulo Freire would smile, and commend us for making his pedagogy come alive in the most dehumanizing of places, a maximum-security prison. I am thankful to Lori Pompa and the staff of the Inside Out Center for creating this program, and for bringing high-quality learning experiences to both traditional undergraduate students and the incarcerated men and women who share that learning experience with them.