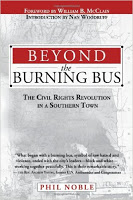

In the process of researching and writing my book, White Allies in the Struggle for Racial Justice, I came across several stories that I was not able to include but where worth honorable mention. One such story is contained in the book Beyond the Burning Bus: The Civil Rights Revolution in a Southern Town by Phil Noble (New South Publishers, 2003). What follows is a review and reflection on this book and the story it tells.

On Mother’s Day, May 14, 1961, group of young people, both Black and White rode on a Trailways bus through the small town of Anniston, Alabama on the route from Atlanta to Birmingham. These Freedom Riders, as they were called, were seeking to make a point of challenging Southern racism by defying So customs of forced segregation on commercial buses. The ride had started in Washington, DC and up to that point, had been relatively calm. As they approached Anniston, they were met by an angry mob of White citizens connected with Ku Klux Klan, who set the bus on fire and then beat the frantic riders as they exited to safety. All of the riders escaped alive but many were badly injured. This horrific event made the national news and put Anniston on the map as place noted for violent racial hatred.

Rev. Phil Noble was a young and relatively new pastor at the First Presbyterian Church. Like many Southern towns, Anniston was economically, geographically, culturally, politically and religiously divided along racial lines, and the burning bus only heightened the racial tensions in the community. Shortly after this incident two black ministers, Rev William McCain and Rev Nimrod Q. Reynolds, called on Rev. Phil Noble to discuss how their churches – Black and White – could work together to bring racial justice to Anniston. The pastors had interacted casually in professional circles, but over the next six years they became partners in the struggle for domestic peace and racial justice in Anniston.

This book tells the story of the courageous men who made up Anniston’s Human Relations

This book tells the story of the courageous men who made up Anniston’s Human Relations Council (HRC) and relates the first two years of the Council’s work made up of five Whites and four blacks who sought to bring down the walls of segregation. For Rev. Noble and the other White members the goal was to avoid the violence that had enveloped other Southern towns like Montgomery and Birmingham. For the Blacks the goal was racial justice. The burning bus incident revealed to both that Anniston could erupt at any moment into all-out chaos if leaders did not act to address both the immediate and underlying issues. As Noble relates the story, for Whites the fact that there was no further outbreaks of violence was progress, but for the Black leader the progress toward desegregation was too slow but still enough to keep them engaged. Noble’s account shows that when courageous Whites and Blacks collaborate to work for the justice, reconciliation is possible. At the same time Dr. King was decrying the inaction of the White moderates in Birmingham in his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”, the White moderates in Anniston stepped up and were able to bring progress with relative peace (there still were many acts of violence and people killed) even in the face of strong segregationist opposition. This is a story not often heard in the days of the Civil Rights South and so is worth exploring.

One of the things that comes through clearly in this book is the different objectives of Blacks and Whites in the Civil Rights period. For the Black community in Anniston and throughout the South, the goal was clear: tear down the walls of segregation and the double standard for Blacks and Whites in all areas of life. For Whites the goals were equally simple: keep order and quiet with the least amount of disruption to their “Southern way of life.” While there may have been many Whites like Noble who had begun to understand the essential wrongness of segregation, it was only when horrific incidents like the burning of the Freedom Riders bus obliterated the myth of Southern tranquility, that such Whites acted. It is a classic case of what Derrick Bell, the reputed founder of Critical Race Theory (CRT), calls “interest convergence.” CRT assumes that Whites only act for racial justice when somehow it is in their self-interest. Anniston’s Mayor and Chief of Police and other leading Whites in Anniston did not have a dramatic conversion to racial equality, but rather were persuaded by the specter and threat of violent outbreak to dismantle their segregationist culture. Furthermore they were convinced by Phil Noble and other moderate Whites that working for racial justice was not only good for the Black community, but also good for the business community and the town’s image in the state and nation.

One of the things that comes through clearly in this book is the different objectives of Blacks and Whites in the Civil Rights period. For the Black community in Anniston and throughout the South, the goal was clear: tear down the walls of segregation and the double standard for Blacks and Whites in all areas of life. For Whites the goals were equally simple: keep order and quiet with the least amount of disruption to their “Southern way of life.” While there may have been many Whites like Noble who had begun to understand the essential wrongness of segregation, it was only when horrific incidents like the burning of the Freedom Riders bus obliterated the myth of Southern tranquility, that such Whites acted. It is a classic case of what Derrick Bell, the reputed founder of Critical Race Theory (CRT), calls “interest convergence.” CRT assumes that Whites only act for racial justice when somehow it is in their self-interest. Anniston’s Mayor and Chief of Police and other leading Whites in Anniston did not have a dramatic conversion to racial equality, but rather were persuaded by the specter and threat of violent outbreak to dismantle their segregationist culture. Furthermore they were convinced by Phil Noble and other moderate Whites that working for racial justice was not only good for the Black community, but also good for the business community and the town’s image in the state and nation.

While I found the book interesting and encouraging, I think two additional aspects of Phil Noble’s account would have added needed depth to the story. First, throughout the book he makes reference to the quiet resistance and passive acceptance of his congregation toward his involvement in the HRC’s desegregation effort. He describes how his church exchanged preachers with black churches and that there were occasional comments for or against his efforts. However, he never discusses his efforts to address the segregationist attitudes within the congregation. For many anti-racist Whites the most daunting and difficult challenge is confronting the racism in their own family and friendships. The question I am most often asked is how to talk to one’s networks about racism; in many White circles such conversation feels difficult if not impossible to address. I would have liked to have heard how Noble sought to address it, regardless how successful he felt his efforts were.

|

| Denmark Vesey |

Second, after fifteen years Rev. Noble left Anniston to pastor a church in Charleston, SC. Historically, Charleston has been a hot bed of racist activity and attitudes. Charleston was a major port for slave ships, the place where the first shots of the Civil War were fired, and the site of landmark court cases challenging disparate pay for black teachers and challenging all white primaries. Denmark Vesey in 1822 led a failed rebellion of slave and free Blacks. And of course, this past summer, a young white man Dylan Roof shot and killed nine Black parishioners of the Emmanuel AME church while they gathered for a prayer meeting. When Phil Noble went to Charleston how did he take the lessons from Anniston and apply them with his congregation in Charleston? Most certainly there were many opportunities, though less dramatic, to continue to address racism in that church as he had in Anniston. Addressing and struggling against racism is not a temporary project but a lifelong endeavor.

Beyond the Burning Busraises the interesting question of how one addresses racism both on a personal and systemic level. Noble was moved to act because of his personal relationships with Black pastors, which in turn led to his involvement in changing the policies and culture of a small town in central Alabama. Even today I suspect in Anniston the struggle continues to address racist attitudes and the systems that support them. Yet it is always important to remember that the actions started

first because people knew each other and acted out of a personal concern that led to systemic change.

Beyond the Burning Busis an interesting read of challenging story that illustrates that with persistence, courage, and committed relationships, racism in its many manifestations can be addressed and in some cases overcome.